My first task for the campaign was to make a map for the armies to fight over. As I’m using the rules of ‘A House Divided’ this meant it would be a straignt area-to-area map of boxes for key locations, linked by roads or railways or seaports. There was also the matter of production points. For this, I decided to make liberal use of Wikipedia and base things primarily on population. After only the briefest of checks, it was clear that info on Scotland’s population, industry and Railway networks of the 1860’s was not of use at all - I’d have to launch a major historical research project! I rapidly decided to use only present-day information, as this was readily available. This would mean certain ‘new towns’ only built after WW2 to ease overcrowding in Glasgow would anachronistically be created in 1861, but I overcame this problem simply enough – I just decided I didn’t care!

Production proved easy enough to work out. Scotland has a population of about 5.2million, so by taking 1 Production Point (PP) as representing about 100,000 people, I quickly managed to knock together a numerical value for each major city, up to a total of 52PP’s on the map. For the rural population, I took the total for each local council region (equivalent to U.S. States, I suppose) and applied it to whichever town was where the council offices were based – the administrative heart where any rural recruits would be assembled anyway.

The overall geography was pretty easy to map out. Scotland is (running south to north) first hilly border-country, then the narrow ‘waist’ of the country at the roughly 40-mile wide Central Belt where most of the population is based - principally in the two major cities of Glasgow in the west, end Edinburgh in the east. Edinburgh is the capital, but Glasgow the largest (and also has the massive shipbuilding industry of the time.) Slightly northwards, and on the east coast we have the small 15-20 mile-wide peninsula of Fife, running eastwards between the Tay and the Forth, and one of the more heavily-populated areas.

After this, the landscape generally builds up into the mountainous Highlands which forms ridges running mainly southwest-to-northeast, but with various isolated routes through them. The west coast is very rugged with lots of islands, but on the east coast you can generally get about 10-20 miles between the mountains and the coast, giving you a coastal corridor running up to Aberdeen. The biggest feature within the highlands is ‘The Great Glen’ which runs nearly ruler-straight from Fort William on the west coast, to Inverness in the Moray Firth. Since the 1745 rebellion by the Jacobites, this has had various forts along it – Ft William at one end, Ft Augustus in the middle, and Ft George outside Inverness at the other end. Pretty useful to control the route!

So, I picked the large cities and towns as ‘areas’ for the map, marking up a photocopied roadmap to sort it out, and drew out the roads & railways as they exist in the modern day (much easier in the Highlands, as the terain usually limits you to only one or two big roads out of each town. I assigned the PPs to each town and got a pretty decent spread. Glasgow was the largest with 6 PPs, but Edinburgh was close behind with 5PPs. Next was Aberdeen in the North, with 4PPS. Eerywhere else got 3PPs (occasional), 2PPs (slightly more common) and 1PP (the large majority). Most places were in the Central Belt, but notable exceptions were Invernes in the Highlands, and Glenrothes in Fife (3PPs each.)

I then spent a quite enjoyable amount of time randomly swapping ownership of various combinations between the Union and the Confederacy. I decided were going to split their initial PP resources 2:1 in favour of the Union, but with the majority of valueless areas going to the Rebels. I also wanted the two factions to be generally ‘coherent’ and connected-up, to prevent small pockets from being overwhelmed. The Rebels would have 17 PPs, and so I immediately ruled out ownership of Glasgow, Edinburgh or Aberdeen, the largest cities. Each of these would have carried between a quarter and a third of the whole rebellion on it’s back alone, so one unlucky battle could see the whole Confederacy collapse! This meant a Union-dominated Central Belt, with a Confederacy-controled Highlands, meaning the terms ‘North’ and ‘South’ for the two sides were rather unusable!

Nevertheless, as you can see from the map below, I generally sorted things out along these lines. The Union has the Borders and the Central Belt, while just northwards of the bottleneck ‘waist’ we have the Rebellious States, with their centres of power in Fife (the ‘Virginia’ of the Rebellion) and in far-off Inverness (like New Orleans, a major city far in the rear, but vulnerable to Naval attack.) The city of Aberdeen has held for the Union, but sits in splendid strategic isolation (like Fortress Monroe just down the coast from Richmond in Virginia) and is kept in supply by the Union’s uncontested seapower.

Next, the armies themselves!

And here it is, drawn on an 8x8 grid! In terms of accuracy to reality, I'd say the map is 10% Reality and 90% Fantasy, but that's all that's needed! I've used the actual town names, placed them relative to each other, and drawn the only significant physical feature, the river Carron, on quite accurately. The road network, woods, hills, and railways are all invented. Pretty much the only modifications for 'reality' came when I looked up some towns on wikipedia and learned some minor fact, but adding in anything like this is pure whimsy - just for the fun of it! It's also worth pointing out that certain thudding inaccuracies will simply be ignored. Stirling, for example, will be mysteriously going without a medieval castle over it's town centre, as 19th Century America tended not to have too many of these!

And here it is, drawn on an 8x8 grid! In terms of accuracy to reality, I'd say the map is 10% Reality and 90% Fantasy, but that's all that's needed! I've used the actual town names, placed them relative to each other, and drawn the only significant physical feature, the river Carron, on quite accurately. The road network, woods, hills, and railways are all invented. Pretty much the only modifications for 'reality' came when I looked up some towns on wikipedia and learned some minor fact, but adding in anything like this is pure whimsy - just for the fun of it! It's also worth pointing out that certain thudding inaccuracies will simply be ignored. Stirling, for example, will be mysteriously going without a medieval castle over it's town centre, as 19th Century America tended not to have too many of these!

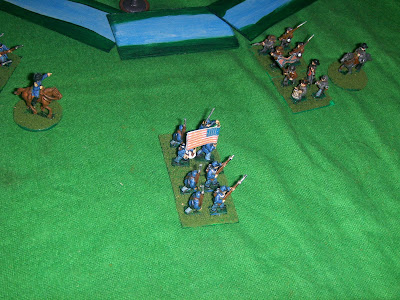

Union troops come rushing up at speed, but the rebel cavalry has potentially turned the flank of the Union line.

Union troops come rushing up at speed, but the rebel cavalry has potentially turned the flank of the Union line. The firing breaks out, and each side loses about half it's force as the militias collapse into helpless disorder. Fighting for the rebels goes best nearest the river.

The firing breaks out, and each side loses about half it's force as the militias collapse into helpless disorder. Fighting for the rebels goes best nearest the river.  The rebels press on, turning to outflank the enemy line...

The rebels press on, turning to outflank the enemy line... In the nick of time, Union reinforcement divisions arrive on the scene. The grey cavalry are scattered and the infantry sent reeling back on their own reinforcements.

In the nick of time, Union reinforcement divisions arrive on the scene. The grey cavalry are scattered and the infantry sent reeling back on their own reinforcements. The hesitating unionists are delayed by small skirmishing groups of Rebels while the remaining infantry form up.

The hesitating unionists are delayed by small skirmishing groups of Rebels while the remaining infantry form up.  The reformed battle-lines clash...

The reformed battle-lines clash... Taking losses, the union keeps it's line straight by giving ground to the screaming rebels.

Taking losses, the union keeps it's line straight by giving ground to the screaming rebels. Disaster for their morale as casualties mount, including the Northern General Wilcox.

Disaster for their morale as casualties mount, including the Northern General Wilcox. The union line is as bent as a snake-rail fence, but can the last division out on the flank save the day?

The union line is as bent as a snake-rail fence, but can the last division out on the flank save the day?  With a crisis at all points on the line, the reinforcing division sends it's brigades in all directions to try and staunch the flow of troops rearward. It quickly descends into chaos.

With a crisis at all points on the line, the reinforcing division sends it's brigades in all directions to try and staunch the flow of troops rearward. It quickly descends into chaos.  Giving the rebel yell, the grey troops are only barely held back by artillery fire point-blank.

Giving the rebel yell, the grey troops are only barely held back by artillery fire point-blank.  Once again the rebels turn the flank by the river, leaving the cannon dangerously exposed, and the disarrayed infantry are in no state to reform.

Once again the rebels turn the flank by the river, leaving the cannon dangerously exposed, and the disarrayed infantry are in no state to reform.  The exhausted Union troops flee to the rear, leaving the field to the exultant Confederates!

The exhausted Union troops flee to the rear, leaving the field to the exultant Confederates!